by Kyle Callahan

After fifteen months of canceled public events due to COVID-19, Poultney’s Fourth of July celebration will return this year with the Lake St. Catherine Boat Parade (held on July 3rd), the Annual 5K Martin Devlin Fun Run (still virtual), and a Float Parade down Main Street. The parade will be followed by a town-wide party at the Poultney Elementary School and capped with a big fireworks display at dusk.

Unfortunately, a bona fide partisan cold war still bedevils our country. The animosity can make Independence Day feel less like a celebration of our shared values and more like a calendar-derived reason to remind each other, once again, of all the ways we differ.

Having claimed the symbols of the United States as their own, the right wing believes the Fourth of July is a time for unabashed nationalism, a day to wave American flags and wear clothes of red, white, and blue. Seeing the holiday as a celebration of every American’s right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, they believe the day should cause a sense of national, tumultuous joy at the righteousness of our nation’s ideals.

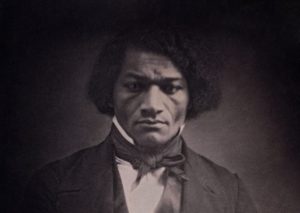

The left wing, on the other hand, sees the Fourth of July as a time to reckon with our nation’s failure to live up to those ideals, which the former slave and avowed abolitionist, Frederick Douglass, called “the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice.” The left compares these declared ideals against the systemic racism infecting our institutions, the military-industrial interests motivating our policies, and the capitalist gluttony corrupting our nation’s health.

In his 1852 speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?,” Douglass summed up the feelings many on the left still have when he told a predominantly white audience (including President Fillmore), “The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common—the rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me… The Fourth of July is yours, not mine… Fellow-citizens, above your national, tumultuous joy, I hear the mournful wail of millions!”

As we’ve highlighted before, this enmity between the political parties is not unique to our time.

In the lead-up to the War of 1812, partisan fever swept across the nation, including Poultney. The local authors of the 1875 history of the town remarked:

“In Poultney…party spirit not only divided the people into political parties, but divided them in their business, social, and indeed in nearly all their public relations… Many carried the feeling so far as to patronize only stores, mill owners, mechanics, and professional men of their party. The women seemed as enthusiastic and determined as the men, and their afternoon and evening visits and quiltings were as exclusively partisan as were the meetings of the rougher sex.”

This rancor bled into the town’s celebration of Independence Day. “The Fourth of July was celebrated each year, as that anniversary returned; but the federalists would celebrate it by themselves, and the democrats by themselves.”

It wasn’t just a matter of celebrating at different houses and fields. The 1875 authors tell us that, “among the younger and more zealous partisans,” a certain level of mischief would occur. On the Fourth of July, the two parties would “spike each other’s cannon [and] steal each other’s rum.”

But when the War of 1812 came along, the town generated a militia of over 100 volunteers, and “federalists as well as democrats enlisted. They differed in political opinions, but it may be put down that they were all patriots, and each in his own way intended to serve his country.”

When this year’s Fourth of July calls us to gather together once again as a community, let us put aside the differences in our opinions to celebrate and remember that “the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice” remain some of the highest ideals to which a nation can aspire.

As Frederick Douglass said at the end of his speech, “I do not despair of this country… While drawing encouragement from the Declaration of Independence, the great principles it contains, and the genius of American Institutions, my spirit is also cheered by the obvious tendencies of the age… I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope.”

Comments are closed.